News

My January Rant

Jan 31, 2013

Lest a month go by in my neglected blog without an entry, allow these few rants on its last day:

Lest a month go by in my neglected blog without an entry, allow these few rants on its last day:

- I've been assiduously at work on bookaworld, making contact with Ethiopian writers and booksellers, and working on the Ethiopian/English volume of Aesop's Fables. I cannot say the same for the IRS which has sat on our application for 501c3 status for over four months. A recent phone call to them resulted in my learning they think there is something wrong with my meticulously prepared application. They won't tell me what. They won't even tell me when they will tell me what, though it looks like it will be around the end of the year! I'd ask for my $400 back, but you know where that would get me.

- Guns. Don't look for substantive changes in gun laws. The Supreme Court has held that the second amendment guarantees individuals the right to own military weaponry. And it will take a constitutional amendment or a new and very different Supreme Court before that changes. And is it my imagination, or am I reading about a fatal shooting just about every day now?

- Syria. Bashar al-Assad has now killed upwards of 60,000 of his own people, making his old man, at a measly 25K or so, look like a wuss. There is a little doctrine called the Responsibility to Protect that frowns on a nation slaughtering its own, and calls upon the international community to do something about it. Is anyone listening?

- The Economy. A very good friend lost his job this week. Don't be fooled by the current bull market. Poverty is increasing. The middle class has shrunk to an all-time (that's ALL-TIME) low. The wealth gap is growing, with most of us stretched thin while a very few enjoy wealth that would embarrass Louis XVI. I say, let the ridiculous sports figures, Hollywood stars and, yes, even the hedge fund managers make their quadrillions a year, if they can get away with it. But there is no excuse for any American to be without the guarantee of a job at a living wage.

- Education, etc. Where to start? When I think of the American lives that we are wasting, when I think of the world's lives that we are wasting (as many as 18 million people, mostly children, die of hunger every year), when I think of all the brain power that goes to waste through preventable wars, hunger, disease, meteorological disasters, and lack of education. This world could be a paradise, if we only saw to the basic needs of one another—clean water, sanitation, nutrition, an education, and a job that pays the bills. Is that so much to ask? Does anyone doubt there is enough to go around?

An Open Letter...

Feb 08, 2010

...to our 535 esteemed legislators:

...to our 535 esteemed legislators:

Today, the Association for Computing Machinery (the world’s largest group of computer professionals) announced the winners of the 2010 ACM International Collegiate Programming Competition.1,2 And guess what? The only non-Russian, non-Chinese school in the top ten was the University of Warsaw (Poland, not Indiana). That’s right. Not only did we not finish in the money, we didn’t even finish with honor.

If you cannot see that these results are the canary in the coal mine, auguring disaster for the future of American innovation and competitiveness, then you are even more clueless than you have led us to believe over the past year. While states are busily disordering their legislative framework in a headlong rush for $4.35 billion in federal support, the pittance for which they are competing3,4; while a lone representative (enabled by the Speaker) threatens to destroy the most successful program of technological innovation in history in order to keep her re-election campaign chest stocked with corporate lucre5,6; our nation has gone from an overwhelmingly dominant position in computer science only a few years ago to tying for 14th place with the likes of the Belarusian State University and the Universidade Federale de Pernambuco.

While you Lilliputian Neros fiddle, Rome burns. If we can’t compete with Russia or China in computers, we can’t compete in biomedicine, weaponry, space applications, finance, manufacturing, entertainment, or any of the other industries which, today, are absolutely dependent on computing know-how. And if our programming and computing skills are not up to those of our two giant totalitarian antagonists, then our national security and our hope for spreading democracy across the globe are in dire peril as well.

This is the pass to which you have brought us, and we have no one to thank but ourselves for not taking you all by the collar and heaving you out that magnificent panelled doorway into a snowdrift.

Update: We are responding! See Want a job? Get a computer science degree. Enrollment in computer science is back on the way up!

____________________

1 Chinese and Russian Universities Claim Nine of Top Ten Spots..., accessed, as were all items footnoted in this entry, Feb 8, 2010.

2 Results World Finals 2010.

3 Race to the Top funding faces obstacles, by James Rufus Koren and Canan Tasci, from the Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, Feb 7, 2010.

4 Pressing for changes to charter school laws, by Nicole Fuller, from the Baltimore Sun, Feb 7, 2010.

5 SBIR Insider Newsletter, by Rick Shindell, Jan 11, 2010.

6 Full Disclosure: I work for a company that contributes its expertise to the SBIR program.

NPP Plank 2: Education

Jun 13, 2009

The U.S. system of universal free public education, developed in the 19th century, is one of the brightest stars in the firmament of American democracy. But even the brightest stars eventually go out, and today the system so suffers from its shortcomings, and the cost of those shortcomings has become so high, that the American system of education finds itself undergoing a sea change.

The U.S. system of universal free public education, developed in the 19th century, is one of the brightest stars in the firmament of American democracy. But even the brightest stars eventually go out, and today the system so suffers from its shortcomings, and the cost of those shortcomings has become so high, that the American system of education finds itself undergoing a sea change.

The most glaring among its shortcomings is its failure to deliver a quality product across the full spectrum of society. Urban, rural, and minority populations have consistently received short shrift. Urban minorities, in particular, have been relegated to what are essentially custodial detention facilities, abysmally underfunded, where generations have been lost to poverty and violence, in a downward spiral of despair.

Though impossible to say just how the education system will appear once the smoke clears, it is safe to speculate that there is a better than even chance that the new system will do a superior job of delivering on the egalitarian promise of universal education. Note, for instance, the excellent work being done by the following schools and institutions:

- The Seed Foundation

- With two boarding schools in D.C. and Baltimore, the Seed Schools take poor urban minority students through a rigorous college-prep program.

- KIPP—The Knowledge Is Power Program

- There are 66 schools in 19 states participating in these open-enrollment, college-prep, K-12, charter schools.

- The Equity Project

- This new NYC charter school will pay elite, committed, and effective teachers $125,000 per year. Stay tuned!

- Teach For America

- TFA takes recent college grads and places them in urban and rural schools where education inequality has been most pronounced, then provides them with lots of support.

The American education system is failing at all levels, not merely in the ghettos and rural backwaters. Our very best students are falling behind internationally, as emerging industrial giants such as China, India, and Brazil pour enormous resources into boosting the educational systems upon which their continued growth depends.

Read All Together Now’s postings on Education to stay abreast of the most exciting developments in this area.

The New Political Party platform proposed here rests, in its essence, on three planks: a minimum wage that is a living wage (see NPP Plank 1: A Living Wage); a commitment to educating all Americans to the fullest extent of their capabilities and aspirations; and universal health care, which will be discussed next time. There will be other planks as well, but these three are the bedrock positions from which progressives must neither waver nor retreat.

The Starting Gate

Apr 17, 2009

From “No Child Left Behind,” we are now on to the “Race to the Top,” the Obama administration’s initiative to improve preK-16 education in America. Students who may be considered “at risk” in our system—lower income students and students of color—now comprise almost half the total student body in our public schools, forcing us to confront the substantial inequities in educational opportunities provided to this population.

From “No Child Left Behind,” we are now on to the “Race to the Top,” the Obama administration’s initiative to improve preK-16 education in America. Students who may be considered “at risk” in our system—lower income students and students of color—now comprise almost half the total student body in our public schools, forcing us to confront the substantial inequities in educational opportunities provided to this population.

The Education Trust, an independent nonprofit organization whose mission is to make schools and colleges work for all of the young people they serve, has provided useful data compilations on all 50 states and D.C.1 These data provide a “starting gate” from which we may compare the progress made (or not) in the coming years. The data include demographic information, scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests which are taken annually by 4th and 8th graders, high school graduation rates, and information regarding resources (teachers, curriculum, funding) available to high- and low-income students.

Their handy state maps2 provide links to full reports on each state and a national summary report, as well as a Quick Look Chart, a one-page table showing the progress (or lack of same) in closing educational gaps over the past ten years or so.

Check out how your state measures up; note (in the national summary report) the alarming extent to which we are failing half our children today; then prepare to take your part in attacking a problem which must be solved if America is to retain relevance, let alone pre-eminence, in the 21st century.

____________________

1 Education Watch: Tracking Achievement, Attainment, and Opportunity in America’s Public Schools, accessed Apr 12, 2009.

2 Links to Education Watch 2009 State Summary Reports, accessed Apr 12, 2009.

The Brain Drain Comes Home

Apr 15, 2009

In a service-based, high-tech world, it’s smarts that keep one country ahead of another, and the U.S. has always prided itself on both local and imported smarts to keep us on top. Our wild west form of democracy rewards the entrepreneurial spirit and, for all our fiscal problems and other societal drawbacks, we do provide a rich, laissez-faire environment for developing individual initiative.

In a service-based, high-tech world, it’s smarts that keep one country ahead of another, and the U.S. has always prided itself on both local and imported smarts to keep us on top. Our wild west form of democracy rewards the entrepreneurial spirit and, for all our fiscal problems and other societal drawbacks, we do provide a rich, laissez-faire environment for developing individual initiative.

Our imported smarts include such worthies as the large contingent of former Nazis, Werner von Braun among them, whom we spirited to our shores at the end of WWII to help us with our nuclear and space programs. We also depend on capturing and retaining students from abroad who come here to study in our famed graduate schools. Together with those we bring here on our H1-B program1 (and applications for that important resource are falling2), these graduate students—among the best and the brightest from their native lands—often find the allurements of our open democracy preferable to returning to countries with significantly fewer opportunities, and are enticed to stick around, ultimately winning a green card and citizenship.

That pool of potential smarts is drying up, however, according to a report from the Council of Graduate Schools.3 Following a precipitous 28 percent drop in the number of graduate school applications from foreign students during the chaotic early days of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, subsequent rates of growth in applications have declined for the last three years, from 12 percent growth in 2006 to 4 percent in 2009.

India and South Korea are among the countries with the steepest decline in applications, having entered minus territory for the first time in 2009 (-9 percent and -7 percent, respectively). We have only held to positive growth in 2009 thanks to increased applications from China (16 percent) and the Middle East and Turkey (20 percent).

Is the bloom off the American rose? Let us hope not. Whether the 21st century will be another American century, a Chinese century, or some other century, it will for certain be a century in which high-tech smarts will drive the advancement of industry and of society. In all the realms of pure and applied science, we will move further toward understanding our world in this century than we have in all the previous ones combined.

Whether that understanding will be put to the service of a saner, more just and equitable world, or merely further the exploitation and misery so prevalent today will depend upon who harnesses those smarts, and our hopes still reside at home. For all our crimes and our shortcomings, and they have been as heinous and as unforgivable as any people’s in history, American exceptionalism is real, and the world knows it.

We expect the drop in the growth of graduate school applications is fallout from the Bush years, when the administration did everything it could to destroy our exceptionalism. It didn’t succeed, and if Obama can fulfill even a portion of his promise, we expect America to return to being the star that burns the brightest in the eyes of a world seeking peace and justice.

____________________

1 H1-B visa, from Wikipedia, accessed Apr 11, 2009.

2 Demand for H1-B visas tumble, by Patrick Thibodeau, from Computerworld, Apr 8, 2009, accessed Apr 13, 2009.

3 Growth in international applications slows for 3rd straight year, Apr 7, 2009, accessed Apr 11, 2009.

Dawn of a New Day

Apr 01, 2009

We took the day off yesterday (Friday, March 27) and we’re glad we did. We were home to receive a phone call from James Carmichael, an aid to Rahm Emanuel in the White House. Back in the heady days of the interregnum we had had the audacity to hope for a position in the new Obama White House and had applied for same on the Change.gov web site. Now they were finally getting back to us, and with an offer we are still finding it difficult to believe.

We took the day off yesterday (Friday, March 27) and we’re glad we did. We were home to receive a phone call from James Carmichael, an aid to Rahm Emanuel in the White House. Back in the heady days of the interregnum we had had the audacity to hope for a position in the new Obama White House and had applied for same on the Change.gov web site. Now they were finally getting back to us, and with an offer we are still finding it difficult to believe.

The Initiative for an Equitable Society will be a new cabinet-level department Obama will announce this week, if he hasn’t already. We were offered the position of Research Manager in the office, where we would oversee fact-gathering for upper management tasked, initially, with three assignments:

- Together with representatives of both houses of Congress, draft legislation establishing a national minimum wage at a level sufficient to support a family of four, proportionally weighted to the varying requirements among the states.

- Together with the Department of Education, identify effective national education innovators in preK-16 and gather them into a Presidential Commission tasked with preparing a blueprint, within 12 months, for reforming the American educational system. The administration guarantees funding will be available as well as their full support in generating any legislation which may be required.

- Together with the Department of Health and Human Services and the new Health Czar, evaluate existing universal, single-payer health care systems around the world, taking from each the features which work to the satisfaction of the populaces involved, and, within 12 months, craft a plan for such a system in the U.S.

And if you believe all that, we have a lovely bridge in New York City we are prepared to part with at a very reasonable price.

All Work and No Play

Mar 24, 2009

No Child Left Behind has had one starkly disturbing effect. Recess has completely disappeared from many American elementary schools, in towns and cities that aren’t even bothering to include playgrounds when planning new structures.1,2 It is fast becoming all academics, all the time, to the manifest detriment of our children’s development.

No Child Left Behind has had one starkly disturbing effect. Recess has completely disappeared from many American elementary schools, in towns and cities that aren’t even bothering to include playgrounds when planning new structures.1,2 It is fast becoming all academics, all the time, to the manifest detriment of our children’s development.

Now, the Alliance for Childhood has published a study that shows this trend infecting kindergarten and even preschool ages. Crisis in the Kindergarten: Why Children Need to Play in School reveals that “what we do in education has little or nothing to do with what we know is good pedagogy for children” [from the Foreword, by David Elkind].

Recess or child-initiated play in Kindergarten and preschool has been reduced to thirty minutes or less out of the school day, while the lion’s share of the day is devoted to literacy and numeracy instruction and to the preparation and taking of standardized tests, tests which are extremely unreliable indicators of anything regarding a child’s future academic prospects.

Children are natural, engaged learners, but we all know what schools can do to those instincts. They are doing it at younger and younger ages all the time, and with dire results. Preschool expulsion rates are three times higher than national rates for K-12, and boys are being expelled four to five times more often than girls. The loss of child-initiated play in our preschool and Kindergarten years stifles creativity and imagination, and excessive instruction is contributing to early frustration and failure.

This report needs to be read by all parents of young children, and then the battle must be joined against the political ideologues whose misplaced emphasis on early childhood instruction contradicts everything we know about how children learn.

____________________

1 Banning School Recess, by Ann Svensen, from FamilyEducation.com, undated, accessed, as other notes in this item, Mar 21, 2009

2 no-recess policies being implemented in u.s. school districts, from adoption.com, undated

As California Goes...

Jan 24, 2009

They’re not the worst—they’re just the first!

They’re not the worst—they’re just the first!

You can view the possible future of our nation by examining the present in California, the traditional trendsetter for the rest of us. Children NOW, “a national organization for people who care about children and want to ensure that they are the top public policy priority,” did just that recently. Their January 6, 2009, press release, “Investing in Children Key to Righting California Economy,” reveals their findings, and they are not pretty:

- A million California children are without health insurance. Every time one of them visits a hospital for a preventable ailment, it costs California $7,000, whereas it would cost only 17 percent of that ($1,200) to provide health coverage for each uninsured child.

- One in five (109,011) high school students in California dropped out in 2007.

- Sixteen percent of California adolescents are obese, costing Californians $7.7 billion annually.

- Fewer than half (48 percent) of California’s 3- and 4-year-olds attend any sort of preschool.

- Meanwhile, the state faces a growing shortage of college-educated workers, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. This means that the income gap between in-demand college grads and the excessive numbers of workers with a high school education or less will continue to grow. In 1980, that difference was 39 percent; in 2006, it was 86 percent.

Whither Education?

Dec 08, 2008

New York Times columnist David Brooks is consistently wrong about life in general, but he is often quite perspicacious when it comes to some of the specifics.

New York Times columnist David Brooks is consistently wrong about life in general, but he is often quite perspicacious when it comes to some of the specifics.

His December 5, 2008, column Who Will He Choose?, concerns Obama’s still-to-be-announced pick for Secretary of Education, a selection we consider more important than the ones he has made so far.

Two camps vie for Obama’s allegiance, according to Brooks. In one camp are the radical reformers, epitomized by Michelle Rhee (whom we wrote about in The War on Tenure), and in the other are those representing the establishment view with the “superficial reforms” characteristic of that camp.

Brooks’s insight comes when he notes Obama has skillfully straddled both camps, practicing what he memorably calls “dog-whistle politics” which sends out reassuring signals that only one side or the other can detect. This, of course, was characteristic of Obama’s entire campaign: He managed to make many of us who were not on the same sides of issues believe we detected signals in his language assuring us he was supporting our priorities.

Progressives have now had a cold shower of reality administered to them through Obama’s choices to date. The posts of Education and Labor are yet to come. They are, in our view, the most important, affecting as they do all Americans in areas—income and education—as much in need of radical reform as any in our system.

Brooks’s money seems to be on Arne Duncan,1 a Chicago reformer, for Education, a selection which he says “will be picking a fight with the status quo.” However, if there are any fans of the status quo still about in the land, they are staying silent in the closet. Even the Establishment knows we are in trouble, and it will take a full spectrum of reforms, as well as, perhaps, a partial systemic collapse, to pull us out of the doldrums into which our education system has been mired for the past two generations.

____________________

1 Arne Duncan, from Wikipedia, accessed December 6, 2008

The War on Tenure

Nov 25, 2008

A war on teacher tenure is about to break out.

A war on teacher tenure is about to break out.

Doug Ross, Superintendant of the high-functioning Detroit charter school, University Preparatory Academy, has said getting rid of tenure is one of two necessary steps to effective education reform, as we reported in The Next Step. Michelle Rhee, the hard-driving chancellor of the Washington, D.C., public schools, and an alumna of the forward-looking Teach for America program, has put her money (obtained from private foundations) where her mouth is, suggesting she will offer teachers pay raises as high as $40,0001 if they will give up their tenure rights.

There probably isn’t a public school principal in the nation who couldn’t point to one or more tenured members of their staff they would fire in a New York minute if they could. In fact, most people involved in public schools—students, other teachers, staff, and paraprofessionals—know who these bad apples are, typically teachers who have been around forever, have long ago lost their taste for children and teaching, and are just coasting along on decades-old lesson plans, or no plan at all.

The problem is that public schools are public and, as such, are inextricably a part of the political process. Teachers’ unions fought long and hard for tenure as a means of protecting their membership against arbitrary and politically or financially based firings that had little or nothing to do with performance. Additionally, classroom performance is devilishly difficult to assess in an ongoing, comprehensive, and objective manner.

Inarguably, our schools—and our children—are in deep trouble. Graduation rates below 50% plague inner-city schools, and the national graduation rate of around 68.6% (2006)2 is nothing to brag about when most decent-paying employment requires more than a high school education. Today’s children are the first generation in America less likely to graduate from high school than their parents,3 and school systems around the world are beating our pants off, particularly in the vital areas of science and math.

Were tenure to disappear tomorrow, we would be no closer to solving these problems. It will take a full-court press on the failures of the public school system—cultural, societal, parental, and political, as well as professional failures—to bring American schools closer to the standards set today in Asian and some European systems.

The Seed School model, which removes inner-city children from their blighted environment, may be what is required on a massive scale to save many of our children. For others the intensive attention paid to students in schools such as Ross’s noted above or the schools DuFour, et al., write about in Whatever It Takes: How Professional Learning Communities Respond When Kids Don’t Learn may be what is required. Certainly, we must recruit and retain the highest level of professionals to staff our systems, and we must pay Michelle Rhee-like salaries to do so.

Title II is a federal program that allocates $3 billion annually to promoting teacher and principal quality. The Education Sector, in its recent report, Title 2.0: Revamping the Federal Role in Education Human Capital (.pdf), recommends a reallocation of those funds to bring, in some cases, revolutionary reform to teacher recruitment, retention, and compensation.

Finally, however, we must confront the failure of the 150-year-old public school model itself—the custodial, plant-based, hierarchical, curriculum-centered (rather than student-centered), technologically backward model that is no longer sustainable in, or relevant to, a 21st century world.

____________________

1 A School Chief Takes on Tenure, Stirring a Fight, by Sam Dillon, from the New York Times, November 12, 2008 (Accessed November 21, 2008)

2 Public High School Graduation Rates, from the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (Accessed November 21, 2008)

3 Counting on Graduation (.pdf), by Anna Habash, from the Education Trust, quoting OECD, Education at a Glance 2007: OECD Indicators, Indicate A1, Table A1.2a (Accessed October 29, 2008)

Now is the Hour1

Nov 16, 2008

A new political dawn is breaking in America. A black Democrat is on his way into the White House with a large mandate—and expectation—for change.

A new political dawn is breaking in America. A black Democrat is on his way into the White House with a large mandate—and expectation—for change.

How did it all happen? A look at three selected national maps will tell a large part of the tale. Open these in separate tabs or windows, so you can go from one to the other. (Hint for Internet Explorer or Firefox users: right click the links):

- United States presidential election, 2004 from Wikipedia. Scroll down to the map.

- United States presidential election, 2008 from Wikipedia.

- Average freshman graduation rate, 2004-2005, by state, from the National Center for Education Statistics.

Now compare this map to the third one, showing rates of high school graduation in the 2004-2005 school year. There are exceptions, to be sure; however, there is a clear correlation between many red states and, in this case, the white states with the lowest graduation rates. Virginia and North Carolina broke away from the solid South this year, and neither state is white. A recent New York Times article sheds light on why this happened, noting that Virginia and North Carolina “made history last week in breaking from their Confederate past and supporting Mr. Obama. Those states have experienced an influx of better educated and more prosperous voters in recent years.... Southern counties that voted more heavily Republican this year than in 2004 tended to be poorer, less educated and white....”2

So there it is and there is our cue for the future: If we want to break the modern red-state dominance over our political system, a dominance that has brought us vast inequities in wealth, lost wars, corporate hegemony, a damaged reputation, a tattered Constitution, and a failed economy; a dominance which today we can only hope we have begun to reverse, then we have to get money into the pockets of working men and women, and we have to provide our nation’s children with a proper education.

A living wage and universal quality education. These must be our priorities in the coming days and years, not misusing our wealth in bailing out banks, propping up failed industries, or committing atrocities against medieval civilizations in order to steal their resources.

We are a nation in the enviable position of being able to end ignorance and want within our borders and in our time. Now, together, we must find the will to do so.

____________________

1 A Christmas Carol—Ignorance and Want. Our illustration is taken from the scene in the Alistair Sim Christmas Carol where the Ghost of Christmas Present opens his robe to reveal two starving children, whom he names Ignorance and Want, huddled at his feet. View the scene on YouTube by clicking the link.

2 For South, a Waning Hold on National Politics, by Adam Nossiter, from the New York Times, November 10, 2008 (Accessed November 11, 2008)

The Worm in Teacher’s Apple

Nov 11, 2008

Here’s how bad it’s gotten. The United States is the “only industrialized country in the world in which today’s young people are less likely than their parents to have completed high school.”1 In other words, as far as educating ourselves, we peaked during the last generation and are now on our way downhill.

Here’s how bad it’s gotten. The United States is the “only industrialized country in the world in which today’s young people are less likely than their parents to have completed high school.”1 In other words, as far as educating ourselves, we peaked during the last generation and are now on our way downhill.

Furthermore, over one in three African-American and Hispanic students fail to graduate high school on time, and overall graduation rates for these populations are abysmal, in some cases under 50 percent.

The report from The Education Trust entitled Counting On Graduation indicates the wide range of expectations set by the states for graduation rates, and the ridiculously low goals they establish for improvements. This latter is owing to a weakness in the No Child Left Behind law which leaves to the states the setting of minimum graduation rate improvements to be met annually. In some cases, the annual targets, if met each year, would not raise graduation rates to their ultimate goals until sometime well after 2100.

The numbers game is not a game, and the next administration will, to our peril, treat education in as cavalier and cynical a manner as the last one has. Neglected human capital winds up in jail, on the streets, on the dole, and in emergency rooms, costing us enormous big bucks out of our pockets, not to mention the unwritten words, the unimagined artifacts, and the stillborn insights which, had we treasured and nourished one another’s potential as we ought, might have accrued to the welfare and delight of us all.

____________________

1 Counting on Graduation, by Anna Habash, from the Education Trust, quoting OECD, Education at a Glance 2007: OECD Indicators, Indicate A1, Table A1.2a (Accessed October 29, 2008)

Toward a New Parent-Teacher Association

Nov 09, 2008

“Research confirms what common sense suggests: parents are central to the educational success of their children.” This conclusion comes from One Dream, Two Realities: Perspectives of Parents on America’s High School, by John M. Bridgeland, et al., from Civic Enterprises in association with Peter D. Hart Research Associates and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

“Research confirms what common sense suggests: parents are central to the educational success of their children.” This conclusion comes from One Dream, Two Realities: Perspectives of Parents on America’s High School, by John M. Bridgeland, et al., from Civic Enterprises in association with Peter D. Hart Research Associates and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The study was based on a survey of 1,006 parents of current or recent high school students from urban, suburban, and rural areas of the country. There are currently 25 million parents who have children in high school. The survey categorized high schools as high performing or low performing based on the proportion of students from those schools who went on to college. This is probably a more defensible criterion today than in the past. A high school education alone is simply not adequate to prepare a student for the demands of a high-tech, knowledge-based, 21st century world.

Among the findings:

- Parents understand that this is a more demanding world than it was 20 years ago (61%). Parents with only a high school degree believe this to be true more often (71%) than do parents with a graduate degree (49%).

- Parents share high aspirations for their children. Again, African-American parents and Hispanic parents consider going to college very important (92% and 90%) compared to 78% of white parents.

- Parents know their involvement is important, those in low-performing schools (85%) even more than parents overall (80%).

- Parents in low-performing schools, not surprisingly, feel more left out of the process then parents in high-performing schools. They feel their children aren’t being challenged or properly prepared for college, and the schools are not doing a good job of communicating or involving the parents or are doing so only superficially;

- All parents want better access and participation in their children’s school lives than they currently have; they want earlier contact and more information during early high school years regarding what it will take to get their children into college; and they want a single point of contact at the school who will maintain close communication with them.

A comprehensive solution to increasing parental involvement must address this problem and must provide creative new methods to solve it. Parents must be encouraged, trained, engaged, and, yes, if necessary, required to be parents. Then the recommendations made by this study to create a truly cooperative environment involving students, teachers, parents, and school support personnel will have a chance of succeeding. And in those instances when proper parenting of a child is simply not in the cards—and there will be many such instances—society must be prepared to provide an alternative.

Side Note: When we were an elementary school librarian, we wrote a comprehensive K-6 curriculum for learning library skills, published it throughout the school, and sent it home, so students and parents understood what was expected. Every item in the curriculum included suggested parental activities to enhance the learning taking place in school. The published curriculum was a breath of fresh air for all who saw it, many of whom expressing surprise and gratitude at seeing and understanding for the first time the shape and process of a full-blown course curriculum. It was ultimately distributed to colleagues across the country. The learning environment, and just what goes on there, is often a great mystery to students and parents alike. Raising the veil on that mystery is a key component in acquiring the cooperation of all parties in this vital undertaking.

The Next Step

Nov 07, 2008

Charter schools, vouchers, school choice, No Child Left Behind, blah, blah, blah. We are awash in jargon and unfunded mandates and a generalized sense of desperation surrounding the state of K-to-post-grad education in America, and with good reason. (See our Panic Time for a few good reasons.) The question is, “What Next?” Because the time for “next” is most emphatically now. As we contemplate a new administration in January, we have an opportunity for a new vision and a new direction in American education. There are people and programs that are already living that new direction, and we will go in search of them between now and inauguration day.

Charter schools, vouchers, school choice, No Child Left Behind, blah, blah, blah. We are awash in jargon and unfunded mandates and a generalized sense of desperation surrounding the state of K-to-post-grad education in America, and with good reason. (See our Panic Time for a few good reasons.) The question is, “What Next?” Because the time for “next” is most emphatically now. As we contemplate a new administration in January, we have an opportunity for a new vision and a new direction in American education. There are people and programs that are already living that new direction, and we will go in search of them between now and inauguration day.

We start with the Progressive Policy Institute and its memo To: The Next President; Re: Closing the Graduation Gap by Giving Schools Greater Autonomy (.pdf), by Doug Ross, Superintendent of the University Preparatory Academy in Detroit, Michigan.

Detroit has an abysmal graduation rate of only 25 percent for its boys, and only 32 percent overall. Better inner-city schools catering to poor Black and Hispanic students still enjoy graduation rates hovering around 50 percent.

Ross’s charter school, on the other hand, which he helped start eight years ago, “graduated 93 percent of its entirely African-American, overwhelmingly poor senior class in June 2007, and enrolled 91 percent of those graduates in college or technical school.” They have now re-enrolled for their second year at rates above the statewide average for all freshmen.

How does he and the 50 other similarly constituted schools throughout the U.S. do it? Ross points to four characteristics they all have in common:

- The schools take full responsibility for motivating urban students to learn, doing what it takes to create powerful relationships between students and teachers.

- They create a school environment where achievement, aspiration, and hard work are socially valued, by obsessively emphasizing that all of their students will learn and that, of course, all will graduate and go on to higher education.

- They make it their business to know how each student is doing academically and socially.

- They do whatever it takes to make sure every student succeeds.

Ross calls on the next president to speak up from his bully pulpit in favor of reform; to supplement the penalities in No Child Left Behind with positive reinforcements and more money; and to bring together coalitions of interested parties to devise strategies for overcoming bureaucratic opposition from local boards and teachers’ unions.

Ross doesn’t underestimate the challenges involved in turning American education upside down; however, he has seen the value of doing it first-hand, and his example deserves study and emulation.

Panic Time

Oct 30, 2008

If anything illustrates the failure of American education over the past thirty years, it is the calibre of elected representatives we have seen passing through the portals of our legislative and executive offices, especially at the federal level. An ignorant electorate elects inappropriate representatives.

If anything illustrates the failure of American education over the past thirty years, it is the calibre of elected representatives we have seen passing through the portals of our legislative and executive offices, especially at the federal level. An ignorant electorate elects inappropriate representatives.

That a man of McCain’s temperament, age, health, and political outlook can be in the running for the presidency of what its citizens like to think of as the greatest country in the history of the world is sufficient argument by itself to condemn our educational system as bankrupt.

And indeed, education in this country is on a steady downhill skid. We are falling behind China and Korea in the highest levels of basic scientific research,1 and graduating too few engineering students.2 We are also lagging behind other western countries in numbers of our citizens graduating from post-secondary colleges and universities. Only three countries associated with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)3 have a higher rate of completing post-secondary education among 45 to 54 year olds than America (Russia, Canada, and Israel); however, nine countries have higher rates among 25 to 34 year olds, and others are catching up.4 High school graduation rates are lower than 50 percent in some inner-city schools.5

Meanwhile, low-end jobs are drying up as computers and robots take over more of the load. Manufacturing is disappearing overseas, taking with it the sorts of assembly line jobs that could be performed with only a high-school education.

Income, health, and education—these are the three pillars of modern civilization, and we are neglecting all of them. Our minimum wage is far below a living wage6; we expend twice what other OECD countries do for health care with signficantly inferior results7; and we fail to prepare our citizens for the demands of the 21st century world.

In turning over our polity to the rapacious instincts of an unregulated capitalism, we have betrayed the social contract that defines a just and democratic nation.

____________________

1 U.S. Innovation: On the Skids, by Gary Anthes, from ComputerWorld, October 21, 2008 (Accessed October 23, 2008)

2 Trouble on the Horizon, from the American Society of Engineering Education, October 2006 (Accessed October 23, 2008)

3 The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development is a member-funded organization comprising 30 countries. Russia and Israel are in the process of joining OECD, but are not yet full members.

4 Changing the Game: The Federal Role in Supporting 21st Century Educational Innovation, by Sara Mead (New America Foundation) and Andrew J. Rotherham (Education Sector), October 16, 2008 (Accessed October 23, 2008)

5 Big Cities Battle Dismal Graduation Rates, from CBS News, April 1, 2008 (Accessed October 23, 2008)

6 Minimum wage increasingly lags poverty line, from Economic Policy Institute, January 31, 2007 (Accessed October 23, 2008)

7 OECD in 2006-2007—Health spending and resources, from OECD (Accessed October 23, 2008)

The Un-Quick Fix

Oct 24, 2008

The fiscal meltdown was a manifestation of a tendency that has increasingly infected American society, probably since the “Me Decade” of the 1970s—a growing inability to defer gratification. The masters of the universe who cooked their books during the 00’s did so in order to artificially boost their stock prices in the short run so they could claim huge performance-based bonuses. They invented impenetrable financial instruments they could quickly lay off in a deadly game of musical chairs, a Ponzi scheme they knew they were playing in a rush to claim nine-figure salaries. Their unwillingness to manage their companies with concern for anyone’s welfare—stockholders, customers, workers, or the company itself—in their mad dash for personal profit resulted in a cataclysm that has shaken the global economic system to its foundations.

The fiscal meltdown was a manifestation of a tendency that has increasingly infected American society, probably since the “Me Decade” of the 1970s—a growing inability to defer gratification. The masters of the universe who cooked their books during the 00’s did so in order to artificially boost their stock prices in the short run so they could claim huge performance-based bonuses. They invented impenetrable financial instruments they could quickly lay off in a deadly game of musical chairs, a Ponzi scheme they knew they were playing in a rush to claim nine-figure salaries. Their unwillingness to manage their companies with concern for anyone’s welfare—stockholders, customers, workers, or the company itself—in their mad dash for personal profit resulted in a cataclysm that has shaken the global economic system to its foundations.

Today, this unwillingness to defer gratification for the value of long-term goals is manifesting itself in one particularly unfortunate way, as noted by the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) in their report, Short-Changing Our Future: America’s Penny-Wise, Pound-Foolish Approach to Supporting Tomorrow’s Scientists.

By now, our nation’s pitiful performance in educating a new generation of mathematicians and scientists is old news.1 We need more scientists with advanced degrees dedicating themselves to basic research; however, we are graduating fewer of them, and they are going over to industry, often with only a master’s degree, where they can make a good deal more money. Our technological future depends on basic scientific research, the kind that brought us fiber optics, the transistor, and the laser. Emerging high-tech sectors such as nanotechnology, biotechnology, and clean energy depend on basic research carried out by scientists with advanced degrees in settings that are financially secure. None of these conditions prevails today in America, largely because of our cultural affinity for the quickest route to the short-term payoff.

By the same token, dedicated postdoctoral academic researchers are paid so much less even than graduates with a master’s degree who choose to go into industry that one cannot blame the university “brain drain” entirely on the pursuit of the quick buck. The PPI’s report makes clear the urgent need we have to bolster our support of education at the high end, as we need to bolster it from preschool through college.

We cannot afford to continue luring our best and brightest to MBA degrees with starting salaries of $92,000 plus, while paying the pittance of $50,000 to postdoctoral research scientists in their mid-30s. If there is no one figuring out the ins and outs of the next generation of high technology products, all the MBAs in the world won’t be able to sell them.

____________________

1 Science and Math Education Needs an Overhaul, Say Candidates During Final Debate, by Sarah Lai Stirland, from Wired, October 15, 2008 (Accessed October 19, 2008)

Why Johnny Still Can’t Read

Oct 21, 2008

The decade has been obsessed with No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the educational reform legislation enacted in the early years of the Bush 2 administration. In a world with increasingly few opportunities for unskilled labor, it has become essential that, for the first time in our history, we must teach all children to a higher standard. NCLB promised to do that through the establishment of clear standards for teachers and students to meet; an exchange of greater funding for more accountability in the schools; and a mechanism in the short run to allow students to transfer out of failing schools.

The decade has been obsessed with No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the educational reform legislation enacted in the early years of the Bush 2 administration. In a world with increasingly few opportunities for unskilled labor, it has become essential that, for the first time in our history, we must teach all children to a higher standard. NCLB promised to do that through the establishment of clear standards for teachers and students to meet; an exchange of greater funding for more accountability in the schools; and a mechanism in the short run to allow students to transfer out of failing schools.

Today, just about everyone is unhappy with NCLB, and for good reasons. Though billions in additional federal funding were authorized for the program, the amount was grossly insufficient to reach NCLB’s goals. Furthermore, far less than even the inadequate amount authorized has been appropriated, with a gap between the two reaching a cumulative $85.7 billion between fiscal year 2002 and 2009.

Standards for academic content and student performance are the linchpin of NCLB, and the program has failed to spur the states to develop clear standards upon which to test teacher, student, and school accountability. In fact, allowing all 50 states to develop their own standards has resulted in chaos and confusion. Performance standards are also at wide variance among the states and are often set at unreasonably low levels in order to better attain the unrealistic 100 percent proficiency required by NCLB. Tests are of low quality and poorly scheduled. And accountability measurements, which can contain sanctions quite damaging to a school, create significant fairness issues owing to the variability of standards and assessments.

Teaching to a single standard will ultimately favor teaching those students on the cusp of meeting those standards, short-changing those who are hopelessly behind or already performing beyond the standard. Also, though socioeconomic status is the most important predictor of student achievement, teachers in poor schools are held to the exact same performance standards as those in rich schools, with no additional resources committed to them.

The student transfer provisions of NCLB represent perhaps the weakest element of the program, with only about 1 percent of students eligible to transfer out of failing schools actually doing so. The problem is there is nowhere to go. By limiting transfers within school districts, most parents see little point in transfering their child from a failing school to a nearly failing school. Though NCLB encourages cooperative agreements between districts to allow students to escape from poor inner-city ones, virtually none of the country’s suburban school districts has agreed to do this. Indeed, NCLB acts as a disincentive to break down economic segregation in our schools.

These and other weaknesses of the existing program are set forth in Improving on No Child Left Behind: Getting Education Reform Back on Track, by Richard D. Kahlenberg, et al., and published by The Century Foundation. Kahlenberg’s first chapter is available free of charge and summarizes the issues discussed above. He suspects the deliberate underfunding and other flaws of NCLB may be a ploy on the part of the Republican administration to set up public schools for failure in order to advance an agenda for privatizing American education. Paranoia? Perhaps, but altogether in keeping with the radical right agenda for shrinking government and privatizing everything in sight.

Kahlenberg’s recommendations for getting NCLB back on track are good ones. However, they are going to cost money. As argued in yesterday’s ATN entry, so will ending poverty and providing national health care. In fact, these incentives are going to require a significant attitude adjustment in the minds of the public and our elected officials. The first step in that adjustment is understanding that attending to these matters will ultimately—and not too distantly—result in a higher standard of living for everyone, as we work together to finally realize the American dream.

Software for Hard Times

Sep 08, 2008

Programming is the most fun you can have with a computer. If you're not a programmer, you may have written a macro in Word or (even better) in WordPerfect for DOS (the greatest software application ever). If so, you have gotten a tiny taste of the power waiting at your fingertips.

Programming is the most fun you can have with a computer. If you're not a programmer, you may have written a macro in Word or (even better) in WordPerfect for DOS (the greatest software application ever). If so, you have gotten a tiny taste of the power waiting at your fingertips.

And if you can combine programming with doing someone some good, well, we can't think of a better way to spend a summer.

Neither, apparently, can the folks at HFOSS—the Humanitarian Free and Open Source Software consortium. Started by a group of open source (that’s “FREE”) software proponents on the computing faculties of Trinity College (Hartford, CT), Wesleyan University (Middletown, CT), and Connecticut College (New London, CT), HFOSS has grown to include efforts from other schools, including the University of Hartford, Bowdoin College (Brunswick, ME), and the George Washington University Institute for Crisis, Disaster and Risk Management (Washington, DC). In 2008, HFOSS offered a 10-week summer internship that provided 10 hard-coding undergraduate students with housing and a $4,000 stipend.1 They will be offering internships again in 2009.

Many of the software programs HFOSS develops2 are included in Sahana, “a web based collaboration tool that addresses the common coordination problems during a disaster, from finding missing people, managing aid, managing volunteers, [and] tracking camps effectively between Government groups, the civil society (NGOs), and the victims themselves.”

The three-college consortium has also received a hefty federal grant ($496,429) from the National Science Foundation “to help revitalize undergraduate computer education.”

HFOSS, Sahana, and the kids at their keyboards represent the sort of imaginative, collaborative, and altruistic endeavors that help us at All Together Now recapture some faith in our future.

____________________

1Students Help Humanity with Open Source Software, from The Wesleyan Connection (Accessed September 5, 2008)

2Project Showcase, from HFOSS (Accessed September 6, 2008)

School Choice; Choice Schools

Sep 03, 2008

“School Choice” is one of those loaded terms that often stands in for the neocon effort to destroy the public school system (along with as many other public benefits—Medicare, Social Security—as it can).

“School Choice” is one of those loaded terms that often stands in for the neocon effort to destroy the public school system (along with as many other public benefits—Medicare, Social Security—as it can).

There is plenty wrong with our public schools, and the notion of school choice—to give it the most positive spin—presents desperate parents with the hope they can move their child to a setting more conducive to learning than the impoverished and violent surroundings far too many students find themselves in today. (The fourth season of The Wire grimly and too-realistically depicts just what our inner-city children, teachers, and school administrators are up against.)

School Choice is a largely empty hope, however, as a report from EducationSector reveals. “Plotting School Choice: The Challenges of Crossing District Lines”1 lays out the very real and usually insurmountable obstacles to broadly implementing a program of real school choice in America. Transportation is a major drawback, as is limited capacity in the accepting schools. Under the best of circumstances, few students can reasonably take part in such programs, leaving the vast majority where they are. And there is little research evidence to support the efficacy of moving students to higher-performing schools.

So what is a society that genuinely cares about all its citizens and is justifiably alarmed at the extent to which it is failing far too many of them to do? One idea is to bring teacher compensation more in line with a strategy to recruit and retain the best candidates. This is the argument put forth by Duke University economist Jacob Vigdor in the fall issue of the Hoover Institution's Education Next. His paper, “Scrap the Sacrosanct Salary Schedule,”2 argues that beginning teachers need to be paid more and they need to reach their peak earning years earlier (as happens in other professions) in order for the system to attract the best and the brightest candidates.

Obama has made education a major consideration in his campaign,3 although his solutions often strike one as rather more of the same and lack the out-of-the-box thinking we need to bring to this issue in the 21st century.

Finally, we may need to adopt programs that reflect the title of a 2004 book on educational reform: Whatever It Takes: How Professional Learning Communities Respond When Kids Don’t Learn.4 We need to rescue significant minorities of our people from lives of ignorance, violence, and despair, and we need to adopt new modes of learning that fully incorporate the brave new tools and techniques available to us. And to do these things, we need to do whatever it takes.

Anything less will hasten our decline in a world that needs us and our example more than ever.

____________________

1Plotting School Choice

2Scrap the Sacrosanct Salary Schedule (.pdf)

3Obama on Education

4Whatever It Takes

Teen Angst

Aug 29, 2008

“My suffering used to be so beautiful. Now it’s just a pain in the ass.” So goes a line from a show we were once in that introduced freshmen to college life.

“My suffering used to be so beautiful. Now it’s just a pain in the ass.” So goes a line from a show we were once in that introduced freshmen to college life.

Kids suffer. We tell them, “Enjoy yourself! It’s the best years of your life.” But they suffer, and we know it. Because we did.

They suffer, to an extent, because suffering is beautiful, in a way, when it is something you can indulge in, and not something which is necessarily visited upon you by outside circumstances. Today, kids are suffering to a great extent because those outside circumstances are impinging upon those “best years” when they ought not to be burdened by the real world.

The Horatio Alger Foundation has just released a report entitled, “The State of Our Nation’s Youth, 2008-2009.” They have been polling teenagers since 1996 on their opinions regarding the nation, their schools, their families, and their own lives, present and to come. The most telling number to report this year is that only 53 percent feel hopeful about their country’s future, down from 75 percent in 2003, the year Bush 2 took us to war in Iraq.

Not surprisingly, 75 percent believe the election will make a large difference for the country although, lacking the franchise, only 12 percent of them pay much attention to the campaigns. The economy and Iraq are the outside worries that are bringing the most pressure to bear on our teens, and the pressure to make good grades and get into the school of their choice is the one that haunts their homework-heavy nights.

In polls like this, the grass is often browner on the other side of the fence. Most of our kids—96 percent—say they are going on to some form of higher education after high school, 93 percent think they will reach their career goals, and 88% are confident about their own futures. Such healthy self-regard may be cause for some relief in the face of their otherwise dim view of the present day.

However, in the face of our persistent militarism; our thralldom to corporate interests that are increasing the gap enormously between the rich and the rest of us; and our apparent inability to work together to confront the educational, environmental, and political challenges that must be overcome if we are to endure, let alone prevail, as a species, I can only echo Hardy’s “Darkling Thrush”:

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

A Half a Million Cheers for Peru!

Aug 21, 2008

That’s how many computers Peru is purchasing, then distributing to the poorest of their poor children throughout the country. They’re the first, biggest, and most important testing ground for Nicholas Negroponte’s One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) program. Peru will spend about $80 million on these systems, each of which will contain a rich variety of application programs, books, games, wireless connectivity to other OLPC’s and Internet connectivity as well.

That’s how many computers Peru is purchasing, then distributing to the poorest of their poor children throughout the country. They’re the first, biggest, and most important testing ground for Nicholas Negroponte’s One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) program. Peru will spend about $80 million on these systems, each of which will contain a rich variety of application programs, books, games, wireless connectivity to other OLPC’s and Internet connectivity as well.

Before the Luddites remind us how it takes more than technology to improve education, be aware that the children who will receive these computers hardly even have schools. They have no books or other equipment, their teachers are not much better educated than they are, and their lives have little or no scope beyond the confines of their remote villages. The world holds its breath in anticipation of what may be wrought by this effort.

The government of Peru is to be highly commended for its vision, its generosity, and its daring. Success is by no means guaranteed, and the Luddites are right when they say that throwing technology at a problem does not solve it. But “the Internet Changes Everything,” and computers hold the potential to revolutionize the education of the masses to the same degree as did the invention of the printing press, and perhaps to an even greater degree.

So let the games begin!

Read the Full Story in Technology Review (free registration required)

Let Us Now Praise ... Greg Mortenson

Jun 30, 2008

If we could live our life over again, we'd want to be Greg Mortenson.

If we could live our life over again, we'd want to be Greg Mortenson.

If you haven't read Three Cups of Tea, by Greg and David Oliver Relin, then run, don't walk, to your nearest neighborhood book store or library and get it, read it, and pass it on to a friend. Then set out your penny jar at the office and get cracking. Greg Mortenson is the power, the inspiration, the miracle behind the Central Asia Institute (CAI), and he has devoted his life to bringing education to rural Pakistan and Afghanistan. He has built dozens of schools, provided scholarships for advanced education beyond the primary grades, trained and employed scores of teachers, provided health care training and services, and developed projects to bring clean water to remote communities.

If you haven't read Three Cups of Tea, by Greg and David Oliver Relin, then run, don't walk, to your nearest neighborhood book store or library and get it, read it, and pass it on to a friend. Then set out your penny jar at the office and get cracking. Greg Mortenson is the power, the inspiration, the miracle behind the Central Asia Institute (CAI), and he has devoted his life to bringing education to rural Pakistan and Afghanistan. He has built dozens of schools, provided scholarships for advanced education beyond the primary grades, trained and employed scores of teachers, provided health care training and services, and developed projects to bring clean water to remote communities.

Starting out on a shoestring, living in his car, handwriting over 500 letters of appeal to potential donors for his first school, Mortenson in a mere 15 years has accomplished more to bring us together and to advance world peace than anyone else we know of. CAI's Mission Statement should be a mission statement for all of us: “To promote and support community-based education, especially for girls, in remote regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan.” And it can be. Go online, learn more about CAI, read that book, then give, to a cause that is quietly reforming one corner of the world, and showing us how to do it planetwide.

Though he is overdue the Nobel Peace Prize, all we can do here is award Greg Mortenson All Together Now's first “Golden A” for Achievement. In his compassion, his farsightedness, and his industry, we see the future of our species, if our species is to have a future at all.

Though he is overdue the Nobel Peace Prize, all we can do here is award Greg Mortenson All Together Now's first “Golden A” for Achievement. In his compassion, his farsightedness, and his industry, we see the future of our species, if our species is to have a future at all.

Locked Out

Jun 27, 2008

Education is the key. Education is the door. Having spent eight years working in public education, we know how abysmally underfunded and neglected it is in this country. What must it be like in other, less fortunate places?

Education is the key. Education is the door. Having spent eight years working in public education, we know how abysmally underfunded and neglected it is in this country. What must it be like in other, less fortunate places?

The World Education Institute Survey of Primary Schools is a collaborative effort among the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, eleven participating countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, India, Malaysia, Paraguay, Peru, Phillipines, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, and Uruguay), and leading international experts.

Among the most significant/surprising findings:

- Half of all primary school pupils in Chile attend private school.

- Expenditure per primary pupil is highest in Chile ($2,120) and lowest in India (under $700). In the U.S., it is over $8,000 and it is arguable whether we get better results than India.

- More than half of the students in India attend schools with no electricity.

- Only about two-thirds of children attend schools with a library.

- Only a median 22.8 percent of schools have computers for students to use with access to the Internet.

- The “typical” teacher is 40 years old with 16 years of education including three years of teacher training and 14 years teaching experience.

- Pupil to teacher ratios range from 59:1 (!) (village schools in India) to 18:1 (Malaysia). The average is 33:1 in towns; 27:1 in village schools.

- One-quarter of schools, serving one-third of pupils, had vacancies in permanent teaching staff at the start of the school year.

The Once and Future Nation?

Jun 12, 2008

The first U.S. oil well was drilled in 1859 and the last rail was laid on the transcontinental railroad ten years later. That decade, which also contained the most destructive war in our nation's history, can be said to have begun the Industrial Revolution in the United States. We can only wonder whether, 200 years later, railroads will still be around. We can be quite sure the oil will be gone.

The first U.S. oil well was drilled in 1859 and the last rail was laid on the transcontinental railroad ten years later. That decade, which also contained the most destructive war in our nation's history, can be said to have begun the Industrial Revolution in the United States. We can only wonder whether, 200 years later, railroads will still be around. We can be quite sure the oil will be gone.

How the social changes will play out over the energy crunch we are facing this generation and the next is anyone's guess—and there are a great many excellent minds at work on the guessing. However, what life was like just before those momentous times is clearly set out for us in our nation's history. The Library of Congress has provided us with an "up-close and personal" view of the hard lives led by our ancestors just before the world-altering events described above. Their Trails to Utah and the Pacific is a primary resource consisting of 49 diaries of pioneers trekking westward across America to Utah, Montana, and the Pacific between 1847 and 1869. There are also maps, photographcs, illustrations, and seven published guides for immigrants.

The diaries are part of the LOC's American Memory series, an invaluable collection of Americana on topics ranging from Advertising to Women's History. Warning: these diaries are eye opening, heart breaking, occasionally as tedious as the journeys themselves must often have been, and quite habit forming.

Just for Fun: M.C. Escher at the National Gallery

Jun 11, 2008

The American National Gallery of Art hosts this educational tour of the works of famed Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher.

The American National Gallery of Art hosts this educational tour of the works of famed Dutch graphic artist M.C. Escher.

This well-designed, chronological tour of a fascinating artist's life and work is a fine example of putting computers to the service of education. And you'll save the fare to D.C.!

State of Play

Jun 04, 2008

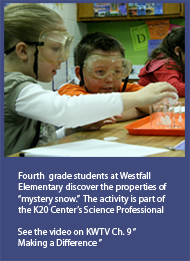

Can computers ever become effective partners in education? The National Science Foundation (NSF) recently described an effort by the K20 Center at the University of Oklahoma that sounds hopeful. McLarin's Adventure is an example of digital game-based learning (DGBL), a research effort that a handful of centers are pursuing around the country.

Can computers ever become effective partners in education? The National Science Foundation (NSF) recently described an effort by the K20 Center at the University of Oklahoma that sounds hopeful. McLarin's Adventure is an example of digital game-based learning (DGBL), a research effort that a handful of centers are pursuing around the country.

The K20 Center has the broad goal of "developing and sustaining innovative, technology-enriched learning communities that motivate and engage K-12 students in pursuing scientific and technical careers." Several university departments worked together to develop the game, in an effort supported by a consortium of schools and businesses across the state of Oklahoma, and funded in large part by the NSF.

SEED Money

May 31, 2008

NYTimes columnist Thomas Friedman introduced us to The SEED School of Maryland in his column today. This statewide public boarding school will open in August 2008 with 80 sixth graders, and will eventually grow to serve up to 400 students in grades six through twelve. This tuition-free, college-prep boarding school experience saves the lives of its mostly urban minority population, as has been proven over the past ten years in the first SEED school in Washington, D.C.

NYTimes columnist Thomas Friedman introduced us to The SEED School of Maryland in his column today. This statewide public boarding school will open in August 2008 with 80 sixth graders, and will eventually grow to serve up to 400 students in grades six through twelve. This tuition-free, college-prep boarding school experience saves the lives of its mostly urban minority population, as has been proven over the past ten years in the first SEED school in Washington, D.C.

Imagine, given the will and the common sense to realize where our own self-interests lie, how many SEED schools we could have supported over the past decade, lifting tens of thousands of children out of lives doomed to poverty, ignorance, and despair, and into a future of hope and accomplishment.

Hey, Teach!

May 30, 2008

Teach for America, a division of Americorps, places top college grads in two-year teaching positions in inner-city and rural schools following graduation. In 2008, they'll place a record 3,700 teachers selected from a recruitment pool of almost 25,000 applicants.

Teach for America, a division of Americorps, places top college grads in two-year teaching positions in inner-city and rural schools following graduation. In 2008, they'll place a record 3,700 teachers selected from a recruitment pool of almost 25,000 applicants.

Copyright © 2008 All Together Now.